By: Barbara Gutierrez

Can the magazine that once highlighted Black success attract readers today? Members of the University community weigh in on the periodical’s past and its return to publication.

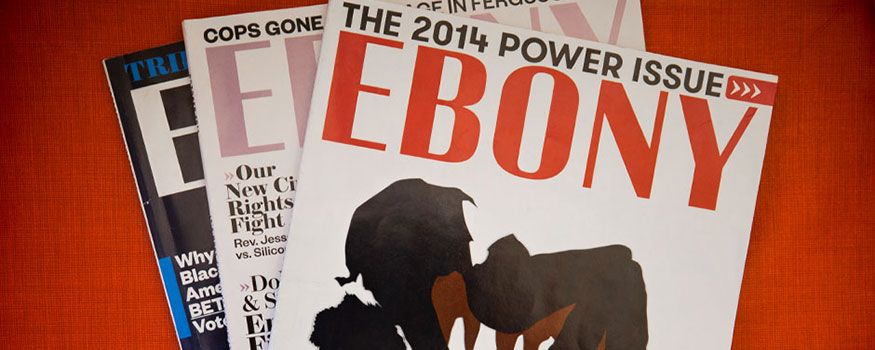

For more than seven decades, Ebony magazine and its sister publication, Jet, were the chroniclers of Black life in the United States. Entertainers, athletes, politicians, civil rights activists, and prominent businesspeople graced its glossy covers. The magazine ceased its print edition in 2019 when it fell into bankruptcy.

Earlier this year, an online version of the magazine was revived thanks to millionaire and former NBA player Ulysses Lee “Junior” Bridgeman, owner of Bridgeman Sports and Media, who won a bid late last year for Ebony’s assets.

Four printed versions of the magazine are slated to be published in 2022. Plans to revive sister publication, Jet, are also in the works.

Olbrine Thelusma, a University of Miami senior studying motion pictures business and interactive media with a minor in Africana Studies and sociology, is thrilled at the resurgence of the magazine.

“I am happy that it is coming back since it will create a space and set a standard that we do not have right now,” she said. “I think it is special because their main goal is to show Black excellence. I don’t see any other publication doing that right now.”

For Tsitsi Wakhisi, associate professor of professional practice at the School of Communication, the revival of the magazine has brought back fond memories. She was a recent college graduate in the late ’70s when she nabbed a job as an editorial assistant with the Chicago-based magazine. She was interviewed by John H. Johnson, founder of the magazine.

“Mr. Johnson was brilliant,” she said. “His vision was to provide a more positive content of the African American community to the African American community.”

At the time, Wakhisi said, most news about Black people was negative and did not reflect the diversity of Black lives. Although there were Black newspapers in various communities, they covered only local news, she said.

“So, if I was in Chicago, I did not know what a Black [person] might be doing in Los Angeles or Kentucky,” she said. “Ebony covered Black America.”

For Wakhisi, working in the Johnson Building on South Michigan Avenue became a source of pride. “The place was full of brilliant minds,” she said. “It was like a Black think tank. Everyone came to meet with Mr. Johnson and other editors.”

While there, she got to see political activist Jesse Jackson and civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael. Although Wakhisi mostly did research for Ebony, Jet, and other Johnson publications, she remembers interviewing members of the musical group The Stylistics. “Working there reinforced my desire to become a journalist,” she said.

At its height, Ebony had a monthly circulation topping 1.2 million.

Donald Spivey, a distinguished professor of history and special advisor to President Julio Frenk on racial justice, believes Ebony was “extremely relevant” to the Black community. He said this was particularly important after Johnson, in the late 1970s, stopped publishing Black World/Negro Digest, a “very hip and historically oriented publication that carried path breaking articles that exuded an Afrocentric perspective,” he pointed out.

“Ebony was a poor substitute but better than nothing,” he added. “It showed some signs of political life near the end but then reverted back to its former self of ‘celebrity watch.’ ”

Criticism of Ebony as a showcase for celebrities and as a bourgeois publication that ignored the daily reality of Black people plagued the magazine, according to Wakhisi. But the magazine seemed to fulfill its mission, which was to showcase Black success.

“Their model was successful,” said Wakhisi. “They wanted more people to aspire to be like the people they featured in the magazine.”

Today’s media landscape keeps changing and many mainstream magazines are having a difficult time holding on to subscribers. Can Ebony’s return be successful?

Wakhisi believes that the magazine has a niche, especially if it expands its coverage to news about Blacks in the Caribbean and Africa. Coverage of current social issues—such as the Black Lives Matter movement and racial inequities in our society—will also attract readers, said Thelusma.

“I agree that mainstream press has broadened its coverage but not to the point that Black people can say they are getting true representation,” said Wakhisi.

Ebony is also partnered with Bloomberg Media and hopes to attract younger readers. “In an announcement, the two companies said the collaboration would include original videos, news articles, a newsletter, and cross promotion on social media. Bloomberg will also play a role in the revival of the Ebony Power 100, an annual list of influential Black Americans, with an hourlong special scheduled for the cable channel Bloomberg Television in November,’’ The New York Times stated in a recent article.

Thelusma believes that young people will support the magazine, especially if special attention is paid to the cover images and the people they select to highlight.

“Young people like to see a good image,” she said. “If it piques our interest, we will support it.”